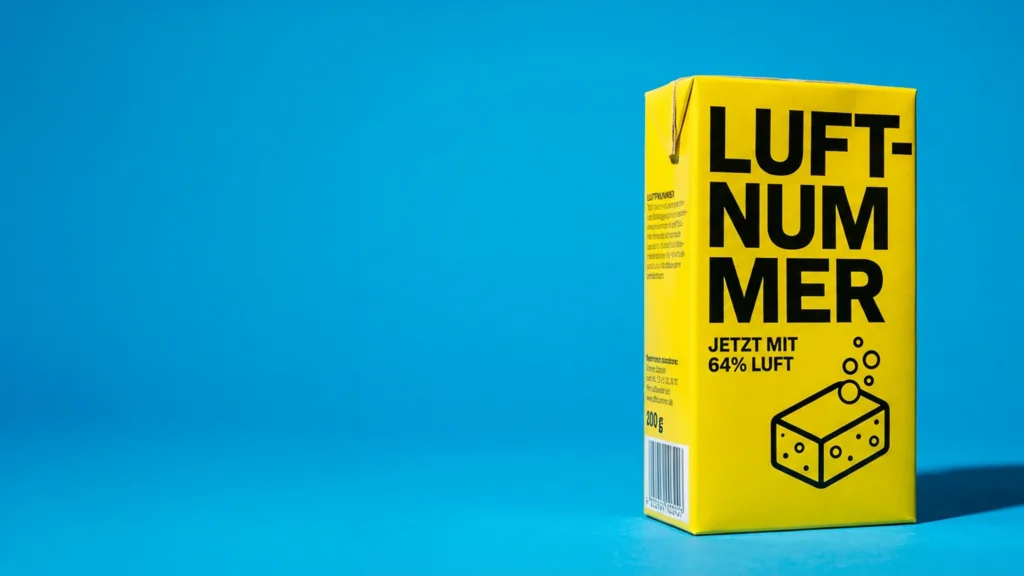

Deception:

Too much air

in the box.

Deception:

Too much air

in the box.

from

When does air in the packaging become an expensive infringement of competition law? Are supermarkets actually directly liable for the deceptive packaging of their own brands, or is this solely a matter for the manufacturer?

If the contents do not deliver what the packaging promises

A discrepancy between the external size and the actual contents is not uncommon in the food trade. Consumer advocates speak of “air numbers”, lawyers of misleading information about the filling quantity. In times of “shrinkflation”, customers and associations are more sensitive than ever before.

But for companies, there is far more at stake than negative PR. If the packaging volume is artificially inflated without there being compelling technical reasons for this, there is a risk of cease and desist letters for competition law infringements. The question of liability is particularly explosive in the case of private labels. Here the retailer slips into the role of quasi-manufacturer and can no longer hide behind its suppliers.

Lots of air around organic tofu

In the proceedings before the Heilbronn Regional Court (Judgment of 10.09.2025 – Ref. Me 8 O 227/24 ), the Baden-Württemberg Consumer Advice Center filed a lawsuit against the retailer Kaufland. The bone of contention was an “Organic Tofu Sesame Almond” from the private label “K-Take it Veggie”.

The piece of tofu (net weight 200 g) had a volume of approx. 202 cm³. The cardboard outer packaging, on the other hand, had a volume of just under 560 cm³. This means that only around 36% of the carton was filled with food. The rest – almost two thirds of the pack – was air.

The retail company tried to defend itself in court by arguing that the packaging was technically necessary (e.g. to protect the vacuum bag or to keep the machine running) and that the manufacturer was also responsible for the filling.

The Heilbronn Regional Court did not accept this argument and prohibited further sales in this product presentation. The decision is instructive as it clarifies the established case law on “deceptive packaging”.

The principle of misconception

The court found that such packaging is misleading. The average consumer infers the quantity of the contents from the size of the packaging. If this expectation is disappointed, this constitutes an infringement of competition law.

The “30% rule” as an indicator

A fixed limit value has been established in case law (e.g. by the Federal Court of Justice): An air content of more than 30 % is generally considered impermissible unless there are compelling technical reasons. Conversely, packaging should be at least two-thirds full (approx. 70%). In this case, however, the filling level was a meagre 36% – far from any tolerance threshold.

The packaging design incriminated here is therefore misleading about the relative filling quantity, because the consumer expects the packaging of a product to be proportionate to the filling quantity contained therein in such a way that the product is filled to significantly more than just two thirds.

Everyday product vs. luxury good

An interesting detail of the ruling is the differentiation between product groups. In the case of luxury items (e.g. chocolates, perfumes or spirits in gift boxes), the consumer often accepts an elaborate presentation with more air, as the representation is part of the product. However, this does not apply to a basic foodstuff such as tofu in a plain cardboard box. According to the court, the customer expects efficiency and content. The court did the math: If the customer had received the expected filling quantity (approx. 70%), the product would effectively have been almost half as expensive – the deception therefore also disguised a price comparison.

What retailers need to check now

The ruling is a wake-up call, especially for the management of private labels. The blanket assertion “This is technically necessary” is no longer sufficient as a defense.

If the air content exceeds 30%, the de facto burden of proof is reversed. The retailer must now explain and prove in detail why the packaging cannot be smaller. Reasons can be, for example

- Protective gas atmosphere (necessary gas volume).

- Breakage protection (required cavity).

- Technical constraints of the filling systems (machine running).

In the Heilbronn case, the retailer was unable to substantiate these reasons sufficiently.

Companies should therefore act as follows:

- Portfolio screening: Check the ratio of content to pack volume for the products. Identify products with an air content of > 30 %.

- Technical documentation: Request detailed justifications for cavities from your suppliers and bottlers before distribution. A general certificate is not sufficient; the necessity must be technically derivable for each product class.

- Transparency offensive: Where a lot of air is technically necessary, the misleading effect can be neutralized by the product presentation. Use viewing windows, transparent films or clear information on the front (“Filling height technically limited” – although this sentence alone often does not protect the product if the air could be avoided).

Conclusion

The “air number” becomes a liability risk under competition law. Retailers who sell private labels are legally treated as manufacturers and must ensure that not only the quality of the food is right, but also that the packaging is honest. The 30% limit is an important guideline. If you exceed it, you need good arguments – or new packaging.

We are happy to

advise you about

Competition law!